HIGHLIGHTS

Untitled

Untitled

Antique mask of cherubs from Guerrero, Mexico

Antique mask of cherubs from Guerrero, Mexico

Sculpture fragment, Mexico

Sculpture fragment, Mexico

Untitled

Untitled

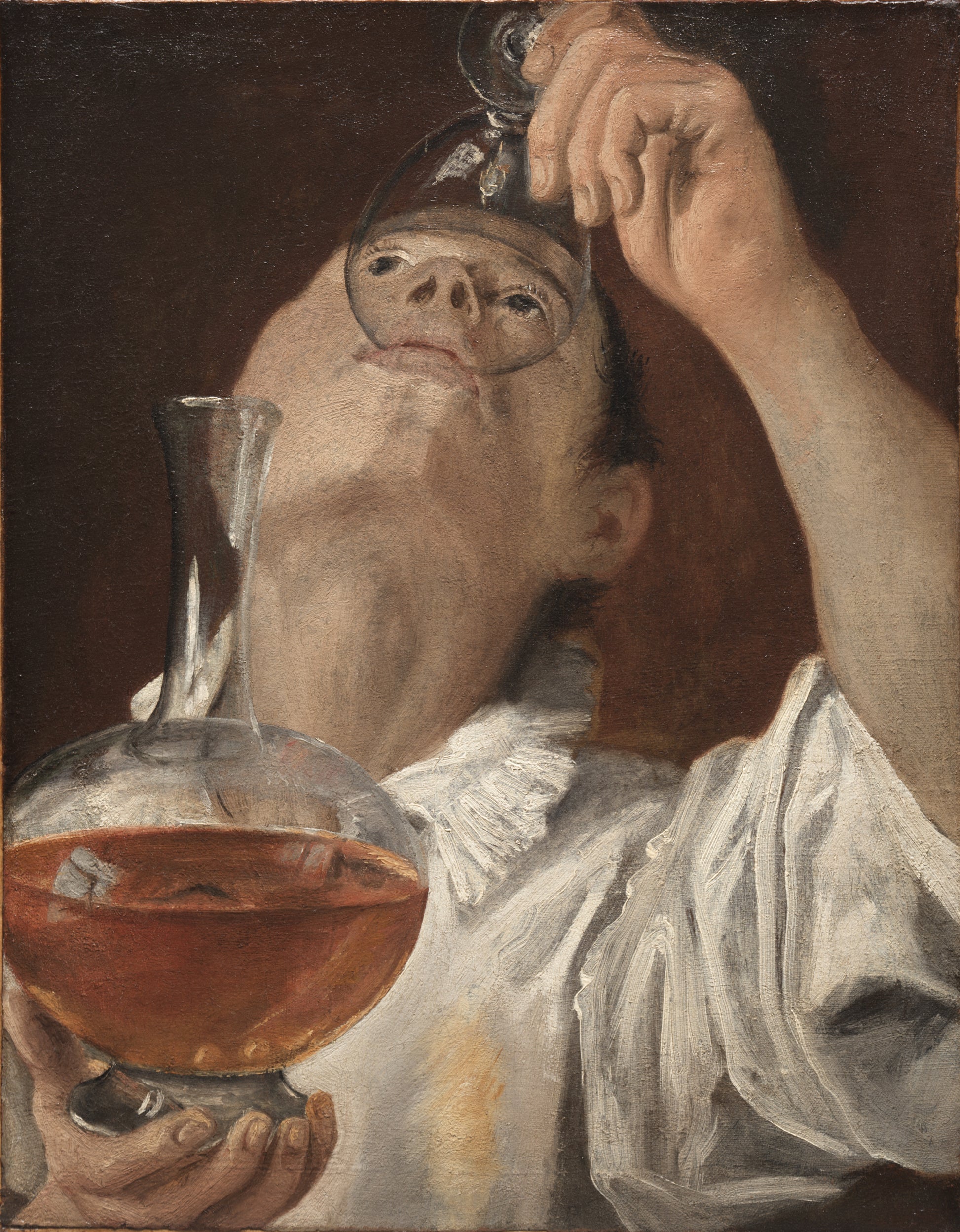

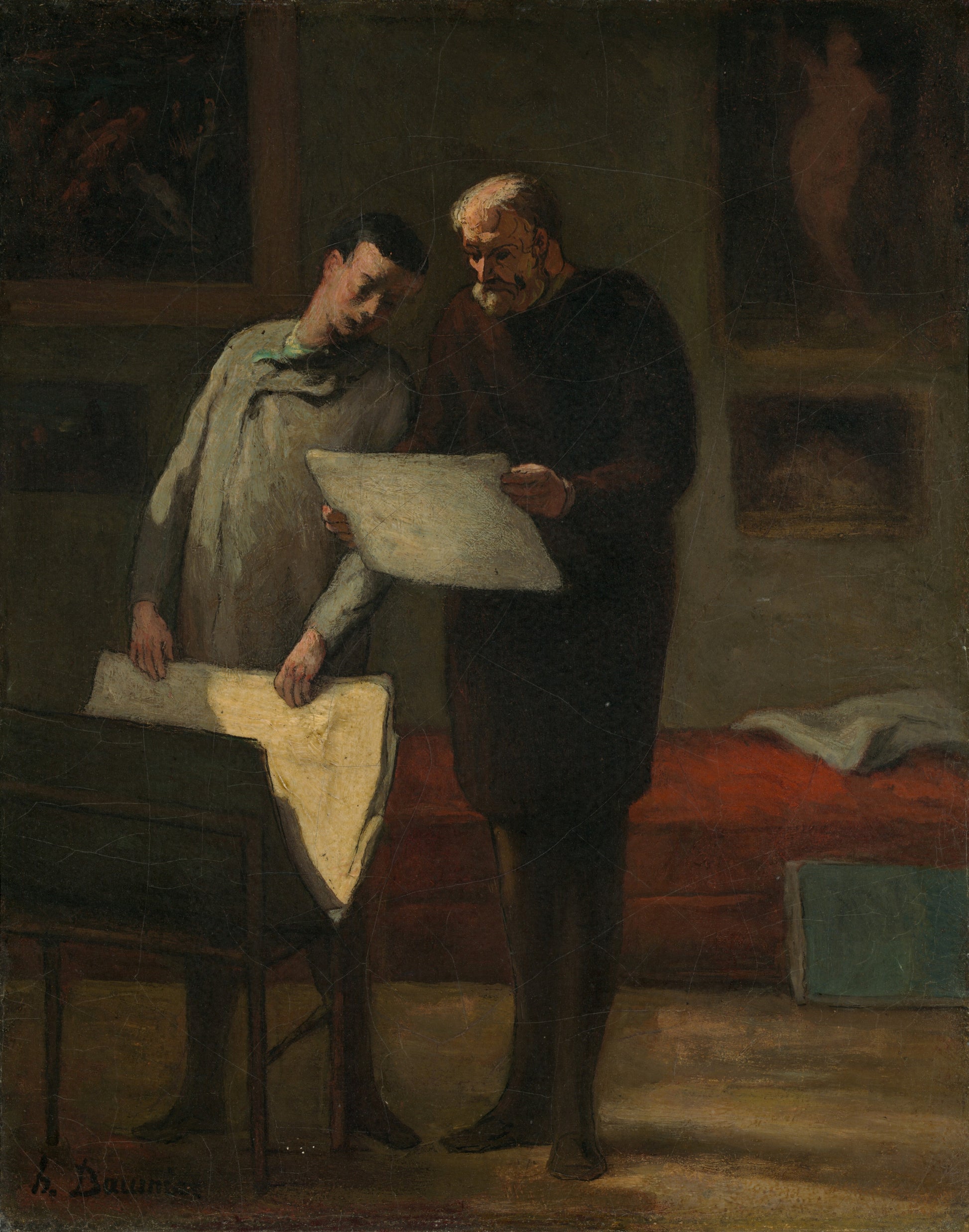

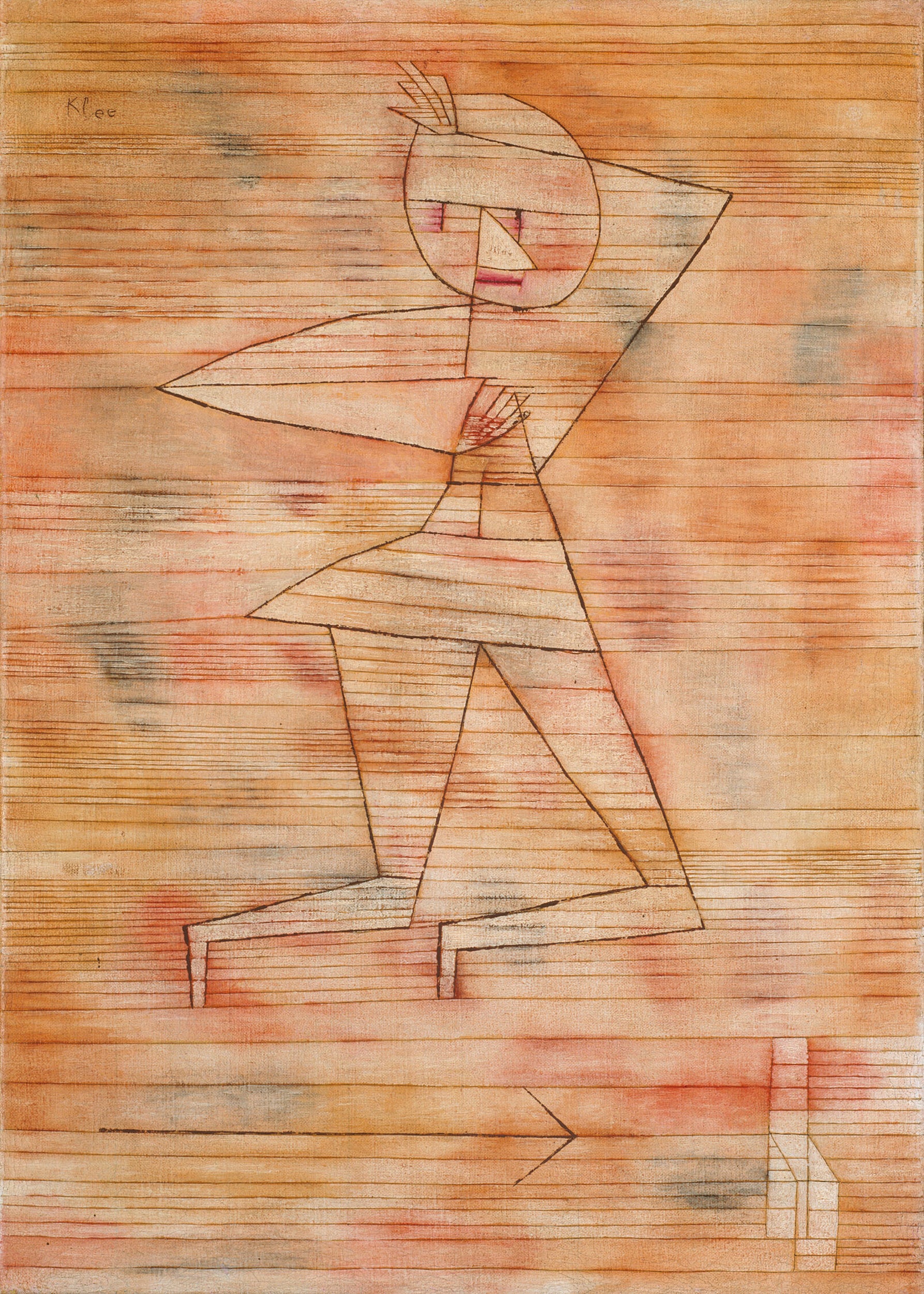

FEATURED REPRODUCTIONS

High-quality, archival prints of art from the Renaissance to the early 20th century starting at $8.

Temptation of Saint Anthony

Hieronymus Bosch

Temptation of Saint Anthony

16th Ce.

Baroque

FEATURED ARTISTS

Marco Torres

About this work

From the artist:

"I am not sure what to say about the pieces and the process. There is pretty much zero conceptual intentionality or self conscious art historical model to any of it. It's basically about applying layers of photoshop to the faces and figures I've always doodled impulsively. What brings all these together (and it really started during the pandemic in 2020) is a desire to try to get some kind of uncanny "flesh effect" through transparent layers and layers of color (the coarse texture of police head or opal transluscence of the snake charmer). I recognize there's some kind of unintentional melancholy or emotional intensity to the facial expressions, and sometimes I am embarrassed that this may seem kitschy or melodramatic so maybe defensively I lean into the grotesque campy sensationalism (cyclopses, snake charmers, sewer shit creatures, cops). There's a self imposed naivety to the whole thing. It feels necessary to make something, since intellectualizing things when I was younger ended up being paralyzing. This the case also for how I am using the digital tools. It's very rudimentary photoshop. Basic brushes, basic effects, just layers and layers. In terms of sources and influences. I am not trying to reference anything. But I'd say what I can look at that makes me want to make more work is Northern Renaissance, Jan Van Eyck et al oil painting. That era's horniness for layering oil to put uncanny flesh on figures still suffering from some pre-renaissance stiffness. Of course this is on top of a primordial Heavy Metal Magazine + Weimar expressionism grotesquerie that I never grew out of."

Untitled Face

Untitled Face

Barburner

Barburner

Santiago

Evans Canales

About this work

It’s hard to say whether this drawing depicts a continuous space or if the woman bent over, bathed in light, is imagined by the man on the couch. The opening to the adjacent room, from where the light floods in, sways along the edges, bending as if the shadows were curtains pulled back by the vision. And though the figures nearly touch, the contrast between the areas of light and shadow that engulf them; the interiority implied by both their postures; and the way the composition is balanced, countering the teetering a triangle stood on its point (the woman) with the solidity of one sat on its side (the man), creates an immeasurable distance between them, turning each into the other’s extreme. The drawing is inspired by Goya’s “Caprichos” and bears particular resemblance to No. 43 in the sequence, “The sleep of reason produces monsters,” which itself may have been based on the frontispiece to 1793 edition of Rousseau’s “Oeuvres Complètes.” The figure in Canales’ version, however, is neither lost to the demons of sleep nor gripped by the throes of inspired creation. Instead, he shares the blank expression of Degas’ drinkers, one of those embodiments of Ennui who, like living ghosts, wait for their oblivion. The drawing’s title—“Barburner”—confirms this reading, but the meaning of the woman remains ambiguous. She also recalls Degas, his pastels of women bathing bent awkwardly over a low tub, only here she is turned away from the viewer and the feeling is less one of intimacy than of estrangement, a growing silence. She exists apart, and the gulf cannot be breached. Desire appears and runs through the image (in the pulsing color of the shadows, the meandering touch of the line), but finds no consummation, remains still unextinguished. Why, then, must it exist?—This seems to me what the drawing is asking.

Jeane Cohen

About this work

The first in a series of sixty-six, so a cover or title page of sorts, overburdened by the task of summing up the whole. The print reminds me of Delacroix, who, after retreating from Paris to the countryside during the revolutions of 1848, set himself the “considerable task” of “paint[ing] bits of nature as we see them in gardens,” anticipating the spirit of Monet’s Nymphéas and, later, Joan Mitchell’s time at Vétheuil. What these artists were after is the self-evidence of nature’s form, the way it appears as given, meaningful in itself. Kant called this its “purposiveness without purpose” and thought it the cause of our feeling of beauty. But the appearance of nature is a dynamic, embodied experience extending through time and space and engaging all of the senses in a way that art by comparison seems hardly aesthetic. And yet the ascetic focus that art demands of the viewer—operating only on the eye and the mind within a discrete expanse of physical space—forces it to discover means of conjuring an imaginary experience, finding purely visual forms that can condense and abbreviate memory. Such that in Cohen’s monotype, I feel the sway of tall grass blown by the wind; the sound of the ocean ebbing flowing; the push and pull of the tide on the shore; I feel the heat of the sun evaporating into the afternoon air, growing brighter and rounder as it traverses its arc, then bursting like a yolk into evening; I feel the falling of dusk and the diffusion of light; I feel the flowers releasing their scent into darkness; I feel the day in its washing away. Away and away.

Sequential Monotype No. 1

Sequential Monotype No. 1

Artists Artists is a new model for the production and sale of art — inspired by the origins of the gallery in the print shops and curiosity dealers that fostered the 19th century avant-garde.